Enhancing corporate responsibility through procurement

CIPS members can record one CPD hour for reading a CIPS Knowledge download that displays a CIPS CPD icon.

Summary

This practical guide will provide P&SM professionals with a high-level view of Corporate Responsibility and how this translates to Responsible Procurement.

Definitions

Corporate responsibility is “being held to account by all stakeholders to act ethically and to deliver positive social, economic and environmental outcomes not just now but with regard to the legacy created for future generations”. (CIPS, 2021)

Responsible procurement is therefore “the process of acquiring goods, works and services that has ethical practice and good governance at its core and takes full account of social, economic, and environmental factors in its decision-making”. (CIPS, 2021)

Introduction

Corporate Responsibility requires an organisation to deliver its business outcomes whilst enhancing its social, economic, and environmental impact with regard to the legacy it leaves behind for future generations. As an evolving and multifaceted subject is also referred to as “Corporate Social Responsibility”, “Corporate Citizenship”, “Environmental, Social, and Governance” (ESG) (MSCI ESG Indexes, 2021) and more generally as “Responsible Business”. Whatever it’s called, the concept of Corporate Responsibility requires an organisation to demonstrate a commitment to high standards and to be accountable to itself, its shareholders and customers and the communities in which it operates.

This drive towards more responsible business practice and the impact of business activity spans business standards including corporate governance and organisational culture, social standards, environmental standards, and animal welfare standards. It places a unique obligation on those whose responsibilities have external influence – including those responsible for managing the procurement process, external suppliers, and supply chains.

Since CIPS published its first paper on this subject in 2007 the Corporate Responsibility agenda has moved centre stage. Increasing transparency, environmental concerns, and the social and economic effect of global trade have highlighted the risk and vulnerability of supply chains, as well as the positive social, economic, and environmental change that suppliers and supply chains can bring – for example, by alleviating poverty.

In developing a more responsible approach to business, each organisation will have its own unique set of challenges, thinking strategically about its own development, social, economic, and environmental impact, and how it will embed the change that is needed for its ambitions to be realised. Each organisation will recognise that some aspects of its thinking and knowledge will be more advanced than others, and that the sentiment of customers, markets and investors is fluid, with national priorities set against common global challenges. As we have seen recently, issues such as the impact of plastic waste, carbon reduction, workplace diversity, and social justice have rapidly come to the fore in the public’s mind.

The fragmented nature of issues and their fluidity has often led to confusion and difficulty in terms of practical application in the workplace. There is no doubt that the pressure for higher corporate standards and “responsible” behaviour has intensified and shows no signs of abating.

This intensification of pressure is being fuelled by:

- increasing transparency and the use of social media to facilitate communication and activism (Thunberg, 2021) on a local, national and global basis

- a recognition of the increasing impact of climate change and the immediacy of action required to mitigate the social, economic, and environmental risk

- higher levels of awareness, expectations, and scrutiny from stakeholders, particularly investors and consumers

- tighter legislative requirements such as the Paris agreement limiting global warming (UNFCC, 2021), UK legislation to reduce carbon reduction emissions (GOV.UK, 2021), plastic waste (UNEP, 2021), corporate governance requirements, and demands for greater transparency (Transparency International, 2021) and provenance

- a breakdown in the level of trust in institutions and commercial organisations, partly fuelled by failings in governance, for example the collapse of Carillion (Accountancy Age, 2021) and the Volkswagen Audi Group vehicle emissions scandal (Cavico & Mujtaba, 2016)

- competitive pressure and the globalisation of markets and trade

- an increasing reliance on external suppliers and supply chains and increased volatility, uncertainty, complexity and ambiguity (VUCA) (Suhayl Abidi, 2015)

While the desire of organisations to behave more responsibly is real and well-intentioned, the practical issues around implementation are often overlooked.

For procurement practitioners in particular, the wide-ranging nature of Corporate Responsibility’s scope and its potential impact often lead to confusion, conflicting requirements, and barriers inside and outside an organisation, which prevents progress from being made. While some of these barriers are real, many result from internal issues that are possible to resolve.

This guide highlights how some of the conflicts and barriers arise, and how they can be avoided or overcome.

The path to responsible business

While becoming a more responsible business is a wide-ranging subject, the scope and the impact we can make in terms of procurement and supply chain is clear. It covers the following four areas:

- business standards and behaviour

- social standards

- environmental standards

- animal welfare standards

This guide highlights the scope of each area in more detail below. The list is not meant to be exhaustive, but it gives a clear indication of its breadth and the areas that procurement professionals are able and expected to influence.

Business standards and behaviour

- Corporate governance: culture, equality, diversity and inclusion, management competency, organisational structure, the effectiveness of controls and management systems, business sustainability

- Ethical practices: personal conduct, conflict of interests, disclosure of sensitive or confidential information, misrepresentation, payment of incentives or inducements, giving or receiving gifts or hospitality

- Legal compliance: the law, contractual obligations

- Abuse of power: dominance of relationships, potential distortion of the market or competition

- Competitiveness: collusion, diminution of free/fair competition, free access to markets

- Supplier diversity: policies relating to supply market diversity or diversity reduction, explicit or implicit bias against particular types or size of enterprise

- Fair dealings: fulfilment of contractual obligations (for example, paying on time)

Social standards

- Employment conditions: level of pay, working hours, treatment of employees under 18 years, freedom of association, use of bonded labour, protection from harassment, contractual terms of employment

- Health and Safety: working environment, safety at work, training and protection of employees, reporting and control systems

- Discrimination: bias in terms of age, religious belief, sexual orientation, gender, race, or disability

- Equality, diversity and inclusion: valuing everyone in the organisation as an individual, where everyone feels able to fully participate and has access to achieve their full potential

Environmental standards

- Environmental impact: waste products, loss of biodiversity, natural habitat, and eco-systems, the use of DNA-modified species

- Climate change: energy use, carbon emissions, other greenhouse gas emissions (GHGs), life cycle carbon intensity, embedded carbon

- Depletion of natural resources: consumption of freshwater, use of oil or chemicals derived from oil, resources that are being used faster than the natural process of replenishment, such as fish stocks, deforestation

- Use or production of dangerous or hazardous substances

Animal welfare standards

- Living conditions: the husbandry, and welfare of animals including how they are housed fed, managed, transported, and ultimately prepared for use.

- Behavioural deprivation: preventing behaviour typical of species in their natural environment

- Inhumane treatment: purpose or action that may cause distress or injury (such as animal testing)

Corporate responsibility, sustainability, and social value

While the terms Corporate Responsibility and Responsible Business are widely used in the private sector, other organisations may refer to Sustainability or Social Value either separately or as part of their Corporate Responsibility or Responsible Business initiatives.

These concepts share the same objectives: to improve social, economic, and environmental impacts.

Sustainability introduces the concept of living or operating within our means to protect the interest of future generations.

Sustainability focusses on how the use and exploitation of natural resources can be reduced – especially non-renewable sources. It also looks at how social and economic outcomes can be improved over the long term; for example, by promoting fair employment practices, skills, and training, or creating opportunities for minority-owned or small businesses.

In 2006 the UK Sustainable Procurement Task Force defined sustainable procurement as “a process whereby organisations meet their needs for goods, services, works and utilities in a way that achieves value for money on a whole life basis in terms of generating benefits not only to the organisation, but also to society and the economy, whilst minimising damage to the environment” (GOV.UK, 2021). This definition is widely used today.

The Public Services (Social Value Act) 2012 (GOV.UK, 2021) requires public sector buyers to consider how social, economic, and environmental benefits could be secured as part of any new procurement. Unlike the accepted definition of Sustainability, the Act limits the scope of what might be considered by the procurement authority to its geographic area and only extends to the procurement of services. However, some public sector organisations incorrectly use the terms “Social Value” and “Sustainability” interchangeably.

Whether in the public or private sector, implementing more sustainable practices, maximising social value through the procurement process or driving more responsible business practices present similar challenges.

Framing the organisational response

As well as creating a shared understanding of what “Responsible Business” means and what aspects are most important, each organisation has to consider what changes are necessary and how it will embed them. There are three areas to consider:

- Operations, including management and staff behaviours and culture, employment practices, the environmental impact of its operations, health and safety practices, and management monitoring and control systems

- Customers and suppliers, and the supply chains they operate within.

- The life cycle impact of the products and services they buy and/or produce (for example, how products are designed for repair rather than disposal)

In framing its response, each organisation needs to establish a set of key principles that will help guide those involved with implementation. These principles are shaped by factors including practical considerations, the character and culture of the organisation, its market position, and its broader business objectives.

These key principles typically include:

- how the concept of Responsible Business fits with the organisation’s broader strategic objectives and goals

- whether the organisation should go beyond the minimum requirement of the law and local standards in each market they are buying from or selling to – for example, Hewlett Packard applies its Standards of Business Conduct globally (Hewlett Packard, 2021)

- how far the organisation should work pro-actively to deliver positive social, economic, and environmental improvement beyond the scope of its direct operations – for example, by sponsoring local community initiatives or by working collaboratively with other peer group organisations to influence policy or market behaviour

- whether the organisation should take action to correct any embedded distortions or bias – for example, by promoting the interests of under-represented groups

- whether the organisation should promote or associate good “corporate citizenship” with the organisation as a whole or with its brands or products – for example, The Waitrose & Partners Foundation (Waitrose, 2021) or Marks and Spencer Plan A campaign (Marks and Spencer, 2021) supermarkets in the UK.

- whether the organisation should adopt a “defensive” approach by prioritising its risks and maintaining parity with market norms and the expectations of its customers

- whether the organisation should adopt the same standards in its own business as those it applies to its suppliers and customers

- prioritising those aspects that are of particular relevance or concern to the organisation and what priority it gives to assessing and managing their impact – for example, McDonald’s Responsible Purchasing Policy begins with a focus on animal welfare (McDonald’s, 2021).

In developing these principles and others, each organisation frames its response to its unique Responsible Business challenges. However, every change programme will have significant internal as well as external dimensions, and require intensive cross-functional co-ordination.

These choices will significantly impact business priorities and determine how Responsible Business translates into a coherent Responsible Procurement strategy implemented by the organisation’s P&SM professionals.

CIPS’ position

The CIPS position on implementing a responsible approach to business is intended primarily for P&SM professionals, but it applies to everyone who has responsibility for managing or influencing the supply of goods or services from an external source. The P&SM professional has a responsibility to gain a thorough understanding of the social, economic, and environmental issues linked to products and services being purchased, to promote awareness across all stakeholders, and to promote positive supply chain impacts to the maximum extent possible.

CIPS believes that P&SM professionals should:

- establish a professional leadership position on social, economic, and environmental issues and the promotion of Responsible Business practices

- ensure all P&SM professionals complete the CIPS “Ethics Test”

- establish priorities based on the social, economic, or environmental risk (or improvement opportunity) of the products and services they buy rather than expenditure alone

- adopt a Code of Ethics (CIPS, 2021) behaviour and apply this across the procurement function and all of those involved in the wider sourcing process

- improve awareness and performance by establishing a minimum set of standards they expect to see adopted by suppliers

- champion “easy to do business with” policies in their organisations, acting as the “voice of the supplier”

- ensure that policies and processes do not inadvertently disadvantage smaller suppliers or those representing minority interests or sectors

- examine sourcing strategies and supplier reduction targets to see if they discourage diversity in the wider marketplace or exclude potentially advantageous smaller suppliers

- ensure that social, economic, and environmental improvement is incorporated into every tender or quotation and influences the selection of new suppliers

- ensure all tender documents require suppliers to demonstrate how they promote equality, diversity, and inclusion in the workplace

- improve the standard and consistency of relationship management by segmenting suppliers carefully so that the level of engagement and interaction is consistent and appropriate to the nature and complexity of the relationship

- adopt a more rigorous assessment of corporate governance and compliance issues before suppliers are selected, and implement effective monitoring after contracts have been awarded

- provide whistleblowing mechanisms so that any abuse of social, economic, or environmental standards in the supply chain can be reported

Barriers to implementation and sources of conflict

Introduction

This section outlines some of the obvious barriers to successful implementation of a more responsible approach to business and their potential root causes. This will help you to identify key actions you can take to overcome these barriers.

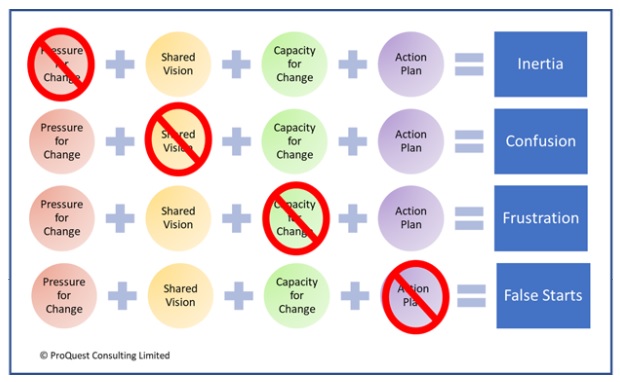

Like any change, implementation of Responsible Business practices is dependent on the presence of several key enablers. The absence of one or more of these leads to some common and easily identifiable problems. We will use the simple model below to examine these in detail.

Enablers of Change (ProQuest Consulting Limited, 2021)

Inertia

Inertia results from a lack of pressure or willingness to change. Perhaps this is because there is no pressure from the outside world, or because such pressure is not recognised or is resisted. The pressure for change within an organisation typically comes from the “top down” – in other words, from leaders who are convinced of the need for change. Ideally change is made proactively, in advance of the need to do it, but often it is made after a weakness has been exposed.

Enabler 1: Creating awareness and understanding

Possible implementation barriers:

- The organisation is disconnected from changes in the market – ie changes are occurring but these demands are not being recognised fully or connected with becoming a “Responsible Business”.

- There is a pull/push from some stakeholders, but not all.

- There is no connection between existing initiatives (eg waste minimisation, energy use reduction, control of hazardous substances) and Corporate Responsibility.

- The organisation believes that Corporate Responsibility is a “management fad” that will pass.

- The organisation considers that it is already advanced in terms of Corporate Responsibility and that no further action is required.

Enabler 2: Building a co-ordinated response to social, economic, and environmental challenges

Possible implementation barriers:

- The organisation has other priorities.

- There is an assumption that Corporate Responsibility initiatives will be addressed functionally as they arise.

- There may not be a clear view of the benefits or doubt that they can be realised.

- The organisation may be unaware of the cost or risk of doing nothing.

Confusion

Confusion results from a lack of shared vision and accountability. This most commonly occurs if Corporate Responsibility develops without the benefit of a coherent framework or without cross-functional input. It will also happen if the motivation for developing better practices is unclear or not deeply grounded in the culture of the organisation.

Enabler 3 : Developing cross-functional understanding

Possible implementation barriers:

- There are gaps in an organisation’s body of knowledge or information.

- There are gaps in strategy, policies, or standards, or insufficient cross-functional input.

- There are gaps in management structures or accountabilities are fragmented.

- Standards conflict or are too open to interpretation.

- There is a lack of consensus about Corporate Responsibility or what needs to be done.

Enabler 4: Defining the role of procurement

Possible implementation barriers:

- The procurement function does not have influence or responsibility for all procurement.

- The social, economic, or environmental impact of related functions is not considered, eg the impact of planning, finance, HR, and legal on suppliers and the supply chain, or the impact of marketing, sales, new product development, or R&D on the specification of the product or service and its design.

- Procurement lacks influence or credibility in respect of Corporate Responsibility.

Enabler 5: Creating policies, standards, and shared understanding

Possible implementation barriers:

- Standards are not aligned or conflict with others (internal/external/peer group or industry).

- Common standards do not exist or are emerging.

- Ownership and accountability for the standards are not clear.

- Standards have been developed by others, have been imposed, and are not realistic or practical or lack clarity.

Enabler 6: Building confidence, trust, and commitment

Possible implementation barriers:

- The “buy-in” and support of suppliers or operational managers is low or absent.

- There is a lack of trust/confidence in those championing Corporate Responsibility.

- There are conflicting messages, priorities, or demands.

- The suppliers lack the incentive to change or adopt new standards.

- Costs and benefits are not distributed equitably (between supplier and buyer).

- The buyer lacks the incentive to change/adopt new standards.

- Corporate Responsibility generates additional work or compliance burden with little value add to those involved.

Frustration

Frustration results from the lack of capacity to change. Capacity can be simply workload or result from a shortage of skills or resource bottlenecks. Because of the cross-functional nature of CSR implementation and the involvement of external suppliers, creating the capacity to change across multiple resources is a particular challenge.

Enabler 7 : Securing available resource

Possible implementation barriers:

- There is initiative overload, poor planning or anticipation, or resource bottlenecks.

- Corporate Responsibility initiatives are given a low priority or their priority conflicts with others (e.g., cost savings).

Enabler 8 : Creating a shared agenda and priorities

Possible implementation barriers:

- Individual roles and responsibilities conflict or overlap.

- Other functions have different priorities, timescales, or constraints.

- Procurement has limited influence over the actions of others.

Enabler 9: Developing the skills to deliver

Possible implementation barriers:

- There is a lack of training/subject awareness.

- It is not clear what new skills/techniques are required or where to get them from.

- Training budgets/resources are constrained, with limited or no access to external specialists or resources.

- It is a new subject so there is limited material, information, or knowledge available.

Enabler 10: Adapting procurement ways of working and developing new approaches

Possible implementation barriers:

- There is a perception that higher social, economic, or environmental standards may lead to higher costs or potentially threaten existing relationships.

- Existing strategies do not take account of the impact of procurement actions, the impact of the suppliers and the supply chains they operate within, or the impact of the products and services bought.

- Resistance to changing practices that conflict or challenge embedded ways of working, for example:

- supplier reduction and consolidation – may conflict with the desire to broaden the supply base or use smaller suppliers

- financial assessments, which focus on the short-term budget impact rather than ‘whole life’ picture over the longer term

- balancing the advantages of local sourcing (e.g., local employment opportunities and economic activity) against the price benefits of sourcing globally

- playing safe – avoiding actions because you are working with limited knowledge or an incomplete picture

- a lack of engagement – because suppliers may not trust procurement’s intentions in respect of improving transparency or supply chain performance.

False Starts

False starts result from a lack of adequate implementation planning. This could be because the subject is difficult to plan or predict, or because the implications and issues that arise once work begins are unexpected and stall the implementation process. Weaknesses across the other enablers also show themselves in an inability to hold a coherent programme of actions together.

Enabler 11: Establish clear accountability

Possible implementation barriers:

- The need to involve other stakeholders is not fully recognised.

- Finding solutions is more complex than originally thought.

- It is not clear who is responsible for what.

Enabler 12: Effective planning

Possible implementation barriers:

- As an emerging subject, it is difficult to plan and resource.

- Change initiatives are not project-managed.

- Targets are set in isolation and/or are too ambitious.

- Other work pressures prevent progress.

- Progress is not measured or communicated.

Enabler 13: Resolving conflicts

Possible implementation barriers:

- There is a lack of experience or expertise.

- There is no process for resolving issues or conflicts.

Overcoming barriers and resolving conflicts

Introduction

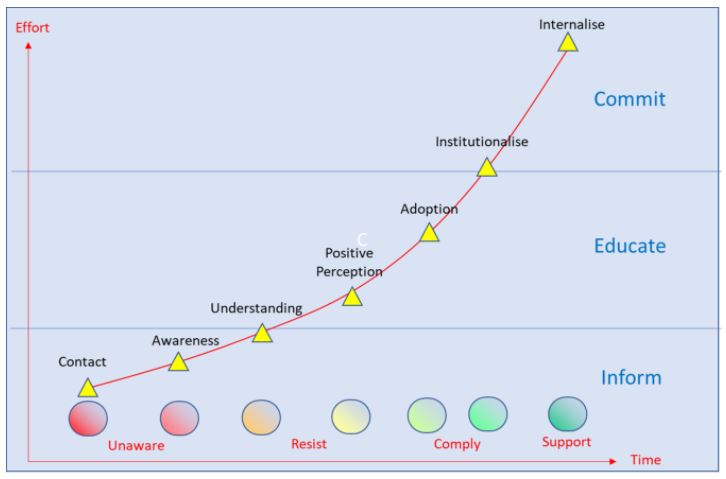

As we have seen, there are numerous reasons why the journey to Corporate Responsibility may be frustrated or fail. As for other change programmes, implementation is a journey, as the graph below illustrates. The task for the P&SM professional is to lead a programme of information, education, and awareness to gain the commitment needed to internalise the change. The aim is to reach a point where Corporate Responsibility is considered to be “business as usual”. In this section, we outline some of the steps to make this happen.

The Commitment Journey (ProQuest Consulting Ltd, 2021)

Management structures

To affect complex and diverse change requires close attention, co-ordination, and leadership from the top. Accountability, roles, and responsibilities should be attributed very clearly so that the strategy and vision at the top level become specific objectives and tasks further down. This involves allocating responsibilities to the existing management structure and in some cases creating new structures to manage implementation. The roles are typically as follows:

- Main board: vision and strategy, advocacy, high-level priorities, and resources.

- Corporate implementation team: cross-functional representation (including procurement), development of standards, resources, prioritisation, high-level plan and objectives, communication, conflict resolution, obtaining functional commitment

- Procurement leadership team: implementation priorities, tools, techniques, training, functional planning, measurement, and reporting, obtaining commitment

- Buying teams/buyers: category/supplier action planning, impact assessment, supplier prioritisation, procurement strategies, supplier engagement, implementation, measurement and reporting, obtaining supplier commitment

- Suppliers: feedback, implementation planning, implementation, measurement, and reporting.

Turning strategy into action

Strategy

At an organisational level, a strategy for Corporate Responsibility gives the procurement function a legitimate case for incorporating social, economic, and environmental improvement into its own strategies and plans. It also helps to provide a cross-functional framework and better co-ordination. In the absence of an organisation-wide approach, procurement may well be able to make some progress and it should seek to incorporate improvement objectives into its policies, functional strategies, and sourcing plans. However, there may be limits to what can be achieved and there is a risk that progress and credibility will be undermined by actions elsewhere in the organisation.

Policy

Policy positions and their associated standards covering the key areas of Responsible Business detailed in this guide are an essential part of the wider engagement process. This helps to make sure that everyone involved has an opportunity to input and consider the impact on their own functions. This should involve all those who directly and indirectly influence the procurement process, supplier selection, the supply chain or who have functional ownership of aspects of the policy within the organisation (for example HR ownership of Social Standards). Determining accountabilities is part of policy development and deployment and is essential for success – CIPS can provide access to example policies and frameworks or point to other organisations that can assist. It helps if the standards are based on international agreements such as those created by the International Labour Organisation (ILO, 2021) or United Nations (UN Global Compact, 2021) but your organisation may wish to go further than these. Some trade organisations, such as those representing the electronics industry, have established common supplier standards (HP, 2021).

Unfortunately, there is no single standard that encompasses all of the issues we have covered in this document.

Planning and prioritisation

Most initiatives fail because they are seen as extra work and less important than other business priorities. Partly this results from not understanding the benefits case clearly, but also in not having realistic and practical plans. In terms of Corporate Responsibility, priorities must be guided by potential risk or impact rather than spend. Very often small changes can make a big difference and make good commercial sense – for example, reducing waste or increasing fuel efficiency will deliver cost savings as well as environmental benefits. Prioritisation is also helped by making sure that SMART (Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Realistic and Timebound) improvement objectives are developed and agreed at category and buyer level, and ideally also with suppliers.

Communication, tools, training, and development

Implementation needs to be accompanied by a programme of communication, education, and in some cases specialist training. Most of the concepts involved are simple to grasp, but the practical aspects of implementation may require new tools and ways of working.

Suppliers are of course part of this process and full consideration should be given to including suppliers in communication and training programmes, and by making tools and techniques available to them as part of the wider effort to improve Corporate Responsibility in the supply chain. An open dialogue will also encourage best practice sharing and innovation that can be applied more widely.

Supplier relationship management

Social, economic, and environmental improvement beyond the boundary of the organisation is dependent on suppliers and the supply chains they operate within (McKinsey, 2021). The relationship between buyer and seller will significantly affect the conversation, the degree of openness, and the willingness of the supplier to work with the buyer and its own suppliers and supply chain partners. Therefore, the need for improved relationship management practices increases significantly. Social, economic, and environmental exposure is not directly related to spend – influence through threat or loss of business may be less effective and the buyer needs to consider more flexible approaches and relationship segmentation practices. Buyers and others involved in managing them should also work hard to communicate consistent messages to establish credibility and trust. Traditional adversarial or arm’s length relationships may not result in improvement.

Sourcing strategy

Social, economic, and environmental priorities should influence sourcing or category strategies and contract awards. Typically, this will be through the adoption of higher standards for new suppliers – while at the same time working with existing suppliers to understand and improve their performance. In most cases, it will be beneficial to work together with the supplier to build capability and awareness rather than to mandate compliance or change suppliers. While this requires more effort and patience, it is more likely to give lasting results. It also demonstrates commitment and will help to build trust and confidence. In some cases, the supplier may present such a high risk to the organisation or its reputation that the only option is to move the business to another supplier with better credentials. Care should be taken not to act too quickly and for the social, economic, and environmental consequences of the decision to be considered. The key message is to act responsibly.

Correcting under representation, bias or adverse market impact

The procurement process is designed to provide access to and attract the best suppliers capable of meeting the requirements and standards of an organisation. However, these processes have often developed in such a way as to create distortions or bias. As a consequence, particular groups or types of suppliers may be under-represented or excluded from fair consideration. For example, the complexity of tender documentation, contracts or insurance limits may prevent smaller suppliers from participating. Framework agreements may also exclude capable suppliers for long periods, causing them to leave the market altogether, potentially diminishing competition over the medium to long term.

Procurement practitioners have to examine the procurement process and their decisions in order to ensure that:

- Social, economic, and environmental requirements and standards are embedded within the sourcing process.

- The internal and external impact of sourcing decisions and strategies is assessed and taken account of.

- There is no discrimination against particular groups of suppliers or types of organisation.

Where groups or types of suppliers are under-represented (for example women-only enterprises or minority-owned businesses), action can be taken to assist those involved to overcome any barriers – for example, by working with them to increase their capability or by positively discriminating in their favour to correct the distortion or bias. Since the goal is to have a level playing field, this can only be justified on the basis that the buying organisation is being disadvantaged by the bias – for example, by excluding capable suppliers – and that such an arrangement is temporary.

Measurement and communication

Measuring the contribution of procurement

Broader considerations need to apply to our assessment of the value that P&SM professionals are delivering.

Corporate Responsibility challenges us to assess the total impact of what we buy and how we buy it covering its impact before purchase, during conversion and use, and after use (“whole life costing”). Against this background, traditional measures of procurement performance such as cost savings are too narrow, and do not reflect broader outputs such as the impact on profit, cash flow, reputation, and increasingly for listed organisations, share price, as well as the external environmental and social impacts of better procurement.

Some organisations are beginning to recognise this. For example, Nestlé has introduced the concept of “Creating Shared Value” (Nestlé, 2021) including the impact of its supply chains and share their commitment and progress in the annual Nestlé CSV Performance Report (Nestle, 2021).

Balanced scorecard

Corporate Responsibility demands that P&SM professionals work more broadly to deliver value and contribute to the operational success of their organisations. Adoption of a balanced scorecard (Kaplan & Norton, 1996) helps P&SM professionals agree on targets and monitor their performance across their key areas. Kaplan and Norton recommend broadening the scope of measures to include a range of financial, customer, and process measures, as well as those associated with the growth and development of its employees. Performance monitoring across these dimensions is intended not only to provide assurance that the business is on track to meet its goals, but also to position it to meet future demands. An example balanced scorecard for procurement might include:

- contribution to profit and cash flow

- risk

- supply chain carbon or waste reduction

- supply chain Social Standards (living wages, welfare standards and education)

- supply chain diversity and inclusivity

- relationship management

- customer/consumer satisfaction

- management and development of people

Whole life costing

Life cycle costing (LCC), also called whole life costing, is a technique to establish the total cost of ownership (CIPS, 2021). It is a structured approach that addresses all the elements of this cost and can be used to produce a spend profile of the product or service over its anticipated lifespan. It is an invaluable aid in making more responsible sourcing decisions in that it considers all cost factors, not just the inbound price paid. For example, a Royal Academy of Engineering report found that the typical costs for owning a building were in the ratio of 1 for construction costs versus 5 for its ongoing maintenance during its expected 30-year life (Evans et al, 1998).

Audit and compliance

As with any initiative designed to improve standards, capability and compliance need to be checked regularly so that P&SM professionals can be confident that the required standards are being met. Internally this is normally achieved by adapting existing audit, compliance, and risk management systems for social, economic, and environmental standards. For external suppliers, additional auditing is required. To reduce costs this can be done by self-assessment, but this typically requires accredited auditors to assess the suppliers' operations on the customer’s behalf. Some accreditation agencies build a database of supplier findings on behalf of several customers, helping to reduce audit costs.

The Sedex initiative (Sedex, 2021) provides a collaborative online forum through which buyers share supply chain information. Similar compliance problems are faced when assessing the provenance of certain products or raw materials. For example, the Forest Stewardship Council provides assurance the wood is derived from approved sources (FSC, 2021). Compliance costs should be considered alongside the cost savings associated with low-cost country sourcing.

Resolving conflicts

Conflicts and uncertainties will arise, particularly during the early stages of implementing a responsible procurement approach. These are much less likely if the ground has been well prepared and policies and standards developed and communicated after cross-functional input. When problems do occur, an organisation should have clear structures for resolving them and communicating the issue and rationale to all of those involved. This helps to develop a body of knowledge and shared understanding. For non-competing/non-confidential issues advice can be also sought from professional or industry bodies.

Desired end state

Corporate Responsibility ultimately has to be embedded as part of an organisation’s normal ways of working and culture, including through policies, systems, and measurement. This often requires special transitional arrangements to build the capability and create the momentum for change before it can become ”business as usual”. The length of this transition depends on the size and complexity of the organisation, but can often take one or more years to complete.

Getting started

Introduction

An organisation-wide ‘Corporate Responsibility’ effort is recommended and in the long term will yield the most impact. However, it is still possible for procurement to begin to make sustainable and important changes that will help improve the organisation’s social, economic, and environmental impact, and may well increase the level of awareness and commitment as well as building the credibility of the procurement function itself.

This section outlines some of the practical steps that procurement can take to start the change process.

The impact of procurement’s actions and behaviour

The first step is to consider what actions procurement can take to improve its own credentials. This should include adopting a Code of Ethical Behaviour across the function and distributing this to all of those who are involved in the sourcing process.

The procurement process itself needs to be transparent, consistently adopted, and auditable. This means the guidelines for procurement need to be clear, written down, and understood by all. Procurement can also make sure that its policies or processes do not inadvertently disadvantage smaller suppliers or those representing minority interests or particular sectors. It should ensure that payment terms are adhered to, and stress the importance this has on the organisation’s reputation as a good corporate citizen. Procurement can also champion “easy to do business with” policies acting as the “voice of the supplier” – for example, by making contracts simpler and consistent or by dedicating a part of the external website to useful supplier information.

There are also steps procurement can take to improve the standard and consistency of relationship management, by segmenting suppliers carefully so that the level of engagement and interaction is appropriate to the nature and complexity of the relationship. Procurement can also examine its sourcing strategies and supplier reduction targets – to see if this is discouraging diversity in the wider marketplace or excluding potentially advantageous smaller suppliers. Procurement can also speak as an advocate of Responsible Business and use a Responsible Procurement Strategy including minimum requirements they expect to see adopted by external suppliers. This may need internal approval, but many of the standards – in terms of the ETI Base Code (ETI, 2021) and Code of Business Ethics (CIPS, 2021) or Environmental Management (ISO 14000) are widely recognised. Such standards can be incorporated as requirements into future tenders for new business.

Procurement can also develop assessment methodologies to help identify the areas of expenditure and suppliers that expose the organisation to social, economic, or environmental risks (eg textile products or raw materials that may involve the use of child labour, or labour subject to the Modern Slavery Act (GOV.UK, 2021)). Advocating membership of a professional body such as CIPS will also encourage the development of high professional standards.

The social, economic, and environmental impact of products and services

Buyers need to prioritise their efforts based on the potential risk or impact of the products or services they buy rather than based on expenditure. Often the first opportunity to improve environmental impact is by controlling waste or excessive levels of consumption, which also has an immediate cost benefit. It is also possible to look at areas where recycled materials can be introduced since they generally consume fewer resources (energy and raw materials) than the original product. Biodegradable products and raw materials will also have a lower environmental impact after they have been used.

Carbon intensity is very high across the built environment, both in the materials used for construction and in the energy efficiency of buildings during their life (UKGBC, 2021). Design standards and alternative construction methods can lead to a significant reduction in carbon and some to “net zero”.

Where materials are made from natural sources, buyers can make sure that these are sustainable or made from recycled content: examples include paper, wood products, food, or electricity. Buyers can also look at travel, car fleet, or other energy-intensive areas to make sure that maximum fuel-efficiency measures are adopted.

Catering services can look to use organic or Fair-Trade product alternatives. Buyers can also work closely with suppliers and marketing or R&D to identify alternative specifications or manufacturing options that have a better social or environmental impact. Often these options will save money as well.

The impact of the suppliers and supply chains you do business with

Again, priority should be decided by potential social, economic, or environmental impact rather than expenditure. You should also consider the supply chain beyond the immediate supplier: for example, if the supplier consumes high levels of energy to provide the product or service being bought, this would be an area of opportunity for discussion and potential improvement. Standards, where they are adopted, can also be used to screen new suppliers and to make sure that policies about gifts and hospitality are clear. Procurement and supplier managers can also agree to improvement targets with suppliers as part of their development objectives.

Buyers can introduce more rigorous external supplier monitoring so that they are aware of any breach of the law or corporate governance that might indicate deterioration in the supplier’s position. Buyers should also make sure that there is a structured process for reviewing contract performance on both sides and make sure that obligations are being met and issues resolved.

Hints and tips

Championing Responsible Business is a real opportunity for P&SM professionals to demonstrate their value across a broad spectrum of initiatives and make a difference to their organisation, its suppliers, products, and the world around them. Below are some handy Hints and Tips that will help to maximise the positive impact you can bring.

- Getting Responsible Procurement on your organisation’s strategic agenda will give you a better chance of co-ordinating the various aspects of standards and policies you will need, and making sure the organisation as a whole is giving its support. However, if this doesn’t materialise there are still practical things you can do to make a start.

- Establish standards cross-functionally by seeking the input of others. Use established standards or emerging frameworks if you can, but don’t be afraid to go further if it suits your organisation. Remember that procurement and the social, economic, and environmental impact of procurement activity are influenced indirectly by the actions of others who may not be part of procurement. Make sure you connect with them as well.

- Work with others, including trade and professional bodies, and share information in a non-competitive way if you can.

- In establishing your priorities, review products/services/suppliers for potential social/economic/environmental impact and the opportunity or risk that they present, as well as the influence you can bring to encourage change.

- Involve suppliers in the analysis. If there is a potentially excellent supplier who is poor on a particular aspect of Corporate Responsibility then work to build capacity rather than switch supplier. This builds trust and credibility.

- Consider social, economic, and environmental issues early. There is most scope when the business case is being prepared or when defining needs and specifications. Engage the market early and build understanding. Early action will be more successful than trying to add things on at the end.

- Use performance or outcome specifications where appropriate to drive innovation and find different solutions.

- Try to give a consistent message to suppliers and stakeholders to create confidence and give practical support and training to those involved.

Conclusion

This practical guide has provided P&SM professionals with a high-level view of Corporate Responsibility – and how this translates to Responsible Procurement. While it is a complex subject with many dimensions it presents P&SM professionals with a real opportunity to demonstrate the value that they can bring to their organisation not only in terms of cost but also reputation, improved risk management, business standards, and supplier innovation. Ultimately it is an opportunity to positively influence the environment and wider communities in which P&SM professionals operate.

Further reading

- CIPS’ Executive Insight Guide on CSR ‘The Ethical Decision’

- CIPS - Sustainable and Ethical Procurement

- CIPS Sustainable Supply Chain

- The Leaders Guide to Corporate Culture (Harvard Business Review) (2018)

- UN Global Compact – Practical Implementation Guide

- ISO 26000 Social Responsibility Guidelines

About the author

Graham Collins FCIPS [LinkedIn]

Graham Collins is an experienced procurement consultant with an established career operating at senior levels within large public and private sector organisations in the UK and abroad.

Graham’s work experience includes a procurement leadership role with the investment bank JP Morgan as VP Sourcing Europe and in the retail banking sector as Head of Strategic Sourcing for the National Australia Bank, where he established a worldwide centre of procurement excellence. Now as a consultant, lecturer and facilitator he supports a wide range of organisations in the public and private sectors, transforming their commercial capability focussing on procurement, commissioning, contract management and responsible procurement as particular specialisms.

Appointed a Fellow of CIPS in 2017, he actively contributes to the development of the profession and is a former Chair of the Central London Branch and editorial board of Supplier Management, the in-house magazine of CIPS. He has authored a number of articles on procurement, contract management, and sustainability.

Underpinning a commitment to transparency and collaboration he founded Orbitá Collaborative Analytics, a supplier data warehouse and collaboration platform exclusively designed for procurement, commissioning, and contract management professionals.

Details can be found at www.orbitacollaborativeanalytics.com

References

- Accountancy Age (2021) Carillion inquiry: missed red flags, aggressive accounting and the pension deficit - Accountancy Age, Accountancy Age, [Online]. Available at https://www.accountancyage.com/2018/02/26/carillion-inquiry-missed-red-lights-aggressive-accounting-pension-deficit/ (Accessed 10 August 2021).

- Cavico, F. J., & Mujtaba, B. G. (2016) Volkswagen Emissions Scandal: A Global Case Study of Legal, Ethical, and Practical Consequences and Recommendations for Sustainable Management. Global Journal of Management and Business Research, 4(2), 303-311. Available at http://gpcpublishing.org/index.php/gjrbm/article/view/431 (Accessed 4 July 2021).

- CIPS (2021) CIPS Professional Code of Ethics, The Chartered Institute Of Procurement And Supply, [Online]. Available at https://www.cips.org/who-we-are/governance/cips-code-of-conduct/ (Accessed 13 July 2021).

- CIPS (2021) CIPS Code of Ethics, The Chartered Institute Of Procurement And Supply, [Online]. Available at https://www.cips.org/employers/ethical-services/corporate-code-of-ethics/ (Accessed 13 July 2021).

- CIPS (2021) CIPS Glossary of Procurement & Supply Terms, The Chartered Institute of Procurement and Supply, [Online]. Available at https://www.cips.org/intelligence-hub/glossary-of-terms (Accessed 7 October 2021).

- Evans, R., Haste, N., Jones, A. , Haryott, R. (1998) The Long Term Costs of Owning and Using Buildings, The Royal Academy of Engineering, London, p5

- ETI (2021) ETI Base Code | Ethical Trading Initiative, Ethicaltrade.Org, [Online]. Available at https://www.ethicaltrade.org/eti-base-code (Accessed 13 July 2021).

- FSC (2021) Homepage, FSC United Kingdom, [Online]. Available at https://www.fsc-uk.org/en-uk (Accessed 13 July 2021).

- GOV.UK (2021) Modern Slavery Act 2015, Legislation.Gov.Uk, [Online]. Available at https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2015/30/contents/enacted (Accessed 10 August 2021).

- GOV.UK (2021) Procuring the future, GOV.UK, [Online]. Available at https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/procuring-the-future (Accessed 13 July 2021).

- GOV.UK (2021) Public Services (Social Value) Act 2012, Legislation.Gov.Uk, [Online]. Available at https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2012/3/enacted (Accessed 13 July 2021).

- GOV.UK (2021) UK enshrines new target in law to slash emissions by 78% by 2035, GOV.UK, [Online]. Available at https://www.gov.uk/government/news/uk-enshrines-new-target-in-law-to-slash-emissions-by-78-by-2035 (Accessed 4 July 2021).

- Hewlett Packard (2021) HPE Standards of Business Conduct, Sbc.Hpe.Com, [Online]. Available at https://sbc.hpe.com/en/ (Accessed 4 July 2021).

- HP (2021) Sustainable Impact, Hp.Com, [Online]. Available at https://www.hp.com/uk-en/hp-information/sustainable-impact.html (Accessed 13 July 2021).

- ILO (2021) Labour standards, Ilo.Org, [Online]. Available at https://www.ilo.org/global/standards/lang--en/index.htm (Accessed 10 August 2021).

- Kaplan, R. and Norton, D. (1996) The Balanced Scorecard: Translating Strategy into Action, Boston, Mass., Harvard Business School Press.

- Marks and Spencer (2021) Delivering Plan A, Marks And Spencer, [Online]. Available at https://corporate.marksandspencer.com/sustainability/plan-a-our-planet (Accessed 10 August 2021).

- McDonald’s (2021) Responsible Sourcing, Corporate.Mcdonalds.Com, [Online]. Available at https://corporate.mcdonalds.com/corpmcd/our-purpose-and-impact/food-quality-and-sourcing/responsible-sourcing.html (Accessed 4 July 2021).

- McKinsey (2021) Sustainability Insights, Mckinsey.com, [Online]. Available at https://www.mckinsey.com/business-functions/sustainability/our-insights (Accessed 13 July 2021).

- MSCI ESG Indexes (2021) Msci.Com, [Online]. Available at https://www.msci.com/our-solutions/esg-investing/esg-indexes (Accessed 4 July 2021).

- ProQuest Consulting Limited (2021)

- Nestlé (2021) Creating Shared Value - Nestlé Annual Report, Nestlé Global, [Online]. Available at https://www.nestle.com/investors/annual-report/creating-shared-value (Accessed 31 August 2021).

- Nestle (2021) CSV Our approach, Nestlé Global, [Online]. Available at https://www.nestle.com/csv/what-is-csv (Accessed 13 July 2021).

- Sedex (2021) Sedex - Empowering Responsible Supply Chains, Sedex, [Online]. Available at https://www.sedex.com/ (Accessed 13 July 2021).

- Suhayl Abidi, a. M. (2015). The VUCA Company, Jaico Publishing House. Available at https://www.researchgate.net/publication/281221689_The_VUCA_COMPANY (Accessed 4 July 2021).

- Thunberg, G. (2021) 'Our house is on fire': Greta Thunberg, 16, urges leaders to act on climate, The Guardian, [Online]. Available at https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2019/jan/25/our-house-is-on-fire-greta-thunberg16-urges-leaders-to-act-on-climate (Accessed 4 July 2021).

- Transparency International (2021) Corruption Perceptions Index, Transparency.Org, [Online]. Available at https://www.transparency.org/en/cpi/2020/index/nzl# (Accessed 4 August 2021).

- UKGBC (2021) Advancing Net Zero - UKGBC - UK Green Building Council, UKGBC - UK Green Building Council, [Online]. Available at https://www.ukgbc.org/ukgbc-work/advancing-net-zero/ (Accessed 13 July 2021).

- UN UN Global Compact (2021) Labour, Unglobalcompact.Org, [Online]. Available at http://www.unglobalcompact.org/ what-is-gc/our-work/social/labour (Accessed 10 August 2021).

- UNEP (2021) UN Environment Programme, [Online]. Available at https://www.unep.org/events/online-event/images-plastic-forever (Accessed 4 July 2021).

- UNFCC (2021) The Paris Agreement, Unfccc.Int, [Online]. Available at https://unfccc.int/process-and-meetings/the-paris-agreement/the-paris-agreement (Accessed 4 July 2021).

- Waitrose Ltd (2021) Waitrose & Partners Foundation, Waitrose.Com, [Online]. Available at https://www.waitrose.com/home/inspiration/about_waitrose/the_waitrose_way/foundation.html (Accessed 4 July 2021).

Related pages

Content related to: Enhancing corporate responsibility through procurement